-

辽西北风沙区是典型的生态脆弱区,位于我国科尔沁沙地南缘,该区水资源不足,气候干燥,植被覆盖率低,大风频繁,是三北防护林体系建设工程的重点治理区域。自20世纪50年代以来,我国一直在实施大规模沙漠化治理工程[1],进行大面积人工造林[2]。1978年以来,我国启动了世界上最大的造林项目“三北防护林带发展计划”[3]。近四十年来,该地区营造了大面积防护林,在生态修复中起着重要的作用。防护林体系的构建是改善沙区生态环境的有效措施,不仅有助于减轻风沙危害[4],防止土壤退化,而且防护林种植有助于改良土壤,增加土壤有机质含量[5],从而影响土壤微生物的活性。

土壤微生物是陆地生态系统的重要生物驱动力之一[6],是土壤生物地球化学循环中最核心的部分[7],是控制生态系统中C、N和其他养分流的关键[8],在推动土壤生态系统的平衡稳定发展方面发挥着至关重要的作用[9]。而且,土壤微生物也是最敏感的指标之一[10-12],较土壤理化特性更能反映土壤质量。诸多研究表明,植被类型、土壤特性以及土壤微生物具有一定的相关性[13-14],土壤理化性质及养分含量的改变会显著影响微生物群落功能多样性[15-16],土壤微生物在提高土壤氮、磷、钾,改善土壤质量等方面也具有重要作用[17]。微生物多样性较高表明土壤养分补充性能较好,且微生物对底物的利用率高[18]。其中,土壤真菌是土壤中的主要分解者之一,能够分解土壤中的有机物(植物残体),为植物提供养分[19],部分真菌有助于提高植物的抗逆性,维持植物正常生长。同时,土壤真菌在促进土壤稳固、团聚体的形成以及改善土壤结构方面具有重要作用[20],对土壤环境乃至整个生态系统都会产生重要影响。在生态系统恢复过程中,真菌群落的变化是一个关键性指标[21],不同树种土壤真菌数量和群落结构具有显著差异[19,22]。除真菌群落多样性和结构之外,微生物功能也是反映土壤质量的重要因子。其中,FUNGuild软件的开发利用有助于我们更好地研究真菌功能类群,且已被众多的学者用于真菌功能群的研究[23-24]。

目前,针对辽西北风沙区防护林的研究主要集中在不同防护林土壤C、N、P垂直分布特征[25],土壤水稳性团聚体质量分数和有机质质量分数方面[26],而针对该地区不同防护林土壤真菌的多样性及功能尚无系统报道。因此,本研究以辽宁省西北部的昌图县付家林场典型的人工防护林,樟子松人工林(Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica Litv.)、油松人工林(P. tabuliformis Carrière)、杨树人工林(Populus ×canadensis Moench)为研究对象,探讨不同人工防护林下土壤真菌群落结构和功能特征,以期为该地区植被恢复和人工林固沙造林树种的选择提供参考。

HTML

-

试验地位于辽宁铁岭市昌图县付家林场,地处科尔沁沙地东南边缘,位于辽宁、内蒙古、吉林三省区交汇处,地势平坦,地貌属辽河冲积平原兼有少量沙丘。土壤类型大部分为风沙土。该地属温带半湿润半干旱大陆性季风气候,最高气温为35.6 ℃,最低气温为−31.5 ℃,降雨集中在7—8月,年平均降水量400~550 mm,年蒸发量1 843 mm,远高于年降水量,极度干旱。该地区的原有植被为少量的灌木和草本,现植被以樟子松和杨树等形成的防风固沙林为主(表1)。

树种

Tree species林分密度

Stand density/

(plant·hm−2)树高

Height/m胸径

Diameter at breast height/cm郁闭度

Crown density/%杨树人工林

Populus × canadensis1 100 15.10 13.30 60 樟子松人工林

Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica275 14.10 33.56 65 油松人工林

Pinus tabuliformis575 10.56 18.50 70 Table 1. Sampling site information

-

2018年7月,分别在试验区选择杨树人工林、樟子松人工林和油松人工林3块样地。分别在每个样地中设置3块20 m×20 m样方,每个样方间距100 m以上,去除表层石块和落叶等杂物,在每个样方内采用“S”形多点取样,利用土钻在树木周围采集0~10 cm土层样品,将土壤样品混匀,作为1个重复,每个处理3个重复,共9个土壤样品,放入无菌自封袋内,做好标记,放入冰盒带回实验室。去除土壤样品中的植物残根、石砾等杂物,研碎混匀,过2 mm筛。一部分土壤样品风干后用于土壤化学性质的测定,一部分土壤样品于4 ℃保存,用于可溶性有机碳的测定,另一部分于−80 ℃冰箱内进行冷藏保存,用于分子生物学的测定分析(3个样地的3个样方的样品均作为一个独立样品进行高通量测序)。

-

pH值采用2.5∶1的水土比,用pH计(TP310)进行测定;土壤全氮含量采用元素分析仪(Elementar, Germany)进行测定;土壤可溶性有机碳含量采用碳氮元素分析仪(TOC,Multi N/C 3100,Analytik Jena AG Multi N/C 3100,Analytik Jena AG)进行测定;速效磷采用碳酸氢钠浸提-钼锑抗比色法测定。

-

土壤总DNA提取采用美国OMEGA公司的MoBio PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MP Biomedicals,Santa Ana,CA,USA)试剂盒,每个样品称取约0.5 g新鲜土壤,按照试剂盒提取步骤进行。用1%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测DNA提取质量(纯度和完整性),用核酸定量仪NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham,MA,USA)检测DNA提取物的浓度和纯度。用引物ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′)和ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′)进行真菌ITS区扩增。PCR扩增体系共25 μL,包含:DNA模板2 μL,各1 μL上下游引物(10 μmol·L−1),缓冲液5 μL,Q5高保真缓冲液5 μL,0.25 μL高保真DNA聚合酶(5 U·μL−1),dNTP(2.5 mmol·L−1) 2 μL,超纯水(dd H2O) 8.75 μL。PCR扩增条件为:98 ℃预变性2 min,然后98 ℃ 15 s,55 ℃ 30 s,72 ℃ 30 s,25个循环,最后,72 ℃延伸5 min。PCR扩增产物经2%琼脂糖凝胶电泳进行检测,并对目标片段进行切胶回收,回收采用AXYGEN公司的凝胶回收试剂盒,产物送上海派森诺生物科技有限公司,采用TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit (Illumina公司)制备测序文库。

-

将QIIME输出的OUT表和物种信息表合并,上传到FUNGuild网站,进行比对和解析真菌群落的营养型、功能分组。依据营养方式划分到病理营养型(pathotroph)、共生营养型(symbiotroph)和降解营养型(saprotroph)3个营养方式以及12个Guild类中,据此进行真菌生态功能群分析。

-

通过使用QIIME软件对原始下机序列进行过滤、拼接、去除嵌合体[27],并对序列长度进行筛选。然后,将有效数据进行OTU归类,对OTUs进行群落丰富度指数和群落均匀度指数分析,包括Chao1指数、ACE指数、Shannon指数和Simpson指数。不同人工林土壤特性、真菌多样性指数和真菌群落组成差异比较采用单因素方差分析(one way ANOVA),不同处理间的差异显著性校验采用最小显著性差异法LSD(Least-Significant Difference)法。使用RStudio v3.5.1软件中的“gplot”和“pheatmap”来构建评价土壤真菌群落间多样性与土壤理化性质的相关性热图。使用RStudio v3.5.1软件中的“vegan”对相对丰度为前50的真菌属以及不同真菌功能类群进行聚类分析并绘制热图。采用Unweighted UniFrac距离来分析不同土壤样品间真菌群落结构的差异,并通过非度量多维尺度(NMDS)进行可视化。采用Canoco 4.5中的典型相关分析(CCA)来研究土壤环境因子与土壤真菌群落功能类群的相关性。

2.1. 土壤样品的采集与处理

2.2. 土壤化学性质的测定

2.3. 土壤DNA提取和高通量测序

2.4. 真菌功能预测

2.5. 统计分析

-

通过测定,发现昌图县付家林场不同类型人工林的土壤化学性质差异显著(见表2),杨树人工林土壤pH值为5.92,显著高于油松和樟子松人工林(P<0.05);杨树人工林土壤可溶性有机碳和速效磷的含量分别为105.46 g·kg−1和16.00 g·kg−1,均显著高于樟子松和油松人工林(P<0.05),樟子松人工林下土壤的全氮含量最高,为1.05 g·kg−1,显著高于杨树和油松人工林(P<0.05),杨树人工林土壤C/N为9.15,显著低于樟子松和油松人工林(P<0.01)。通过比较,发现杨树人工林能显著增加土壤pH、土壤可溶性有机碳和速效磷的含量,降低土壤C/N。

树种

Tree speciespH值

pH value可溶性有机碳

DOC/(g·kg−1)全氮

Total N/(g·kg−1)碳氮比

C/N ratio速效磷

Available P/(mg·kg−1)杨树人工林

Populus ×canadensis5.92±0.11aA 105.46±7.81aA 0.85±0.08bA 9.15±0.26bB 16.00±1.80aA 樟子松人工林

Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica5.57±0.21bA 83.42±18.42abA 1.05±0.10aA 11.41±0.31aA 3.77±1.43bB 油松人工林

Pinus tabuliformis5.53±0.17bA 80.10±32.32bB 0.97±0.07abA 11.79±0.49aA 3.09±0.98bB 注:表中数据为均值±标准差(n=3),不同小写字母表示不同处理之间差异显著(P<0.05),不同大写字母表示不同处理之间差异显著(P<0.01)。 Table 2. Soil properties for different plantation forests

-

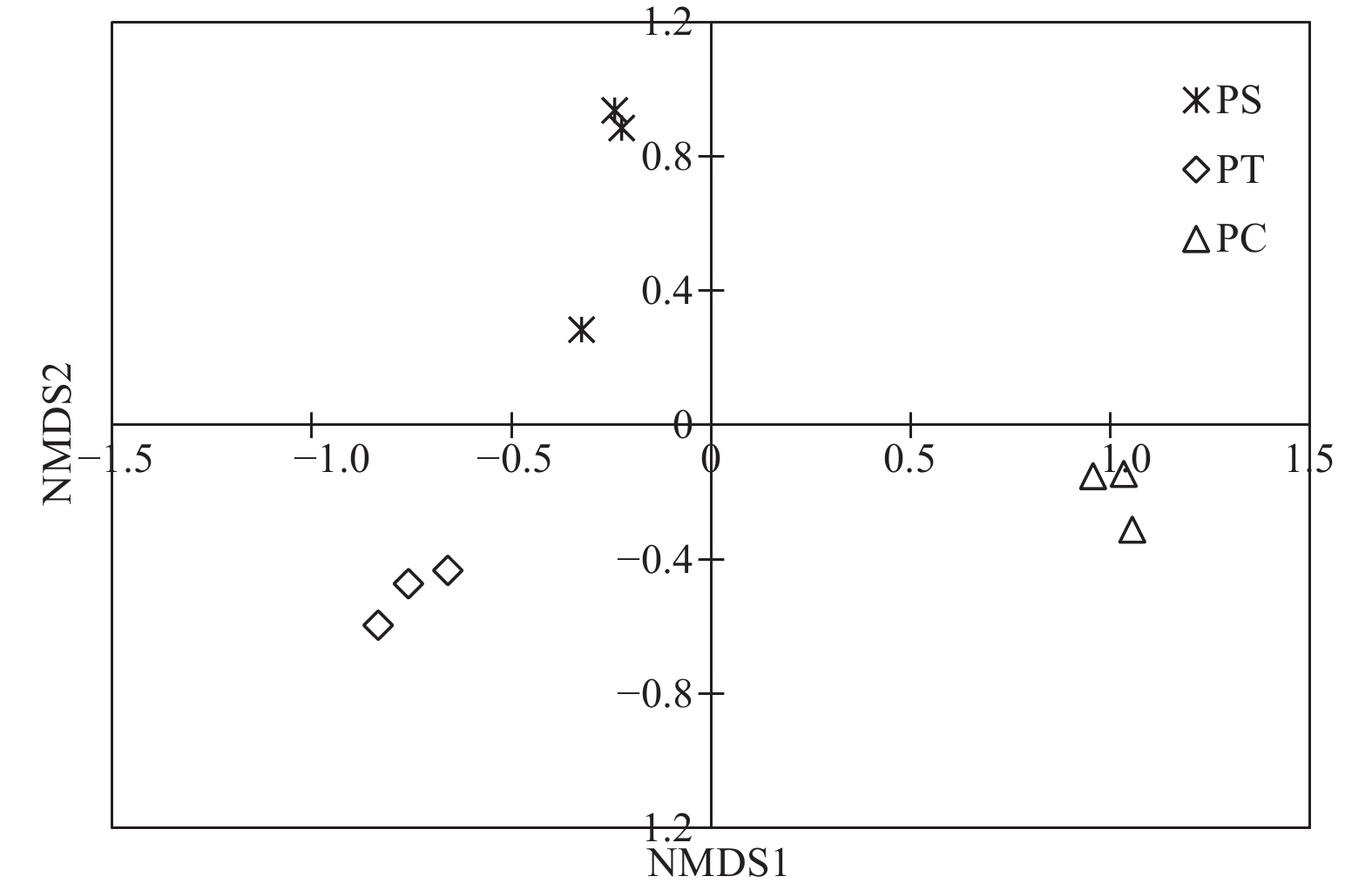

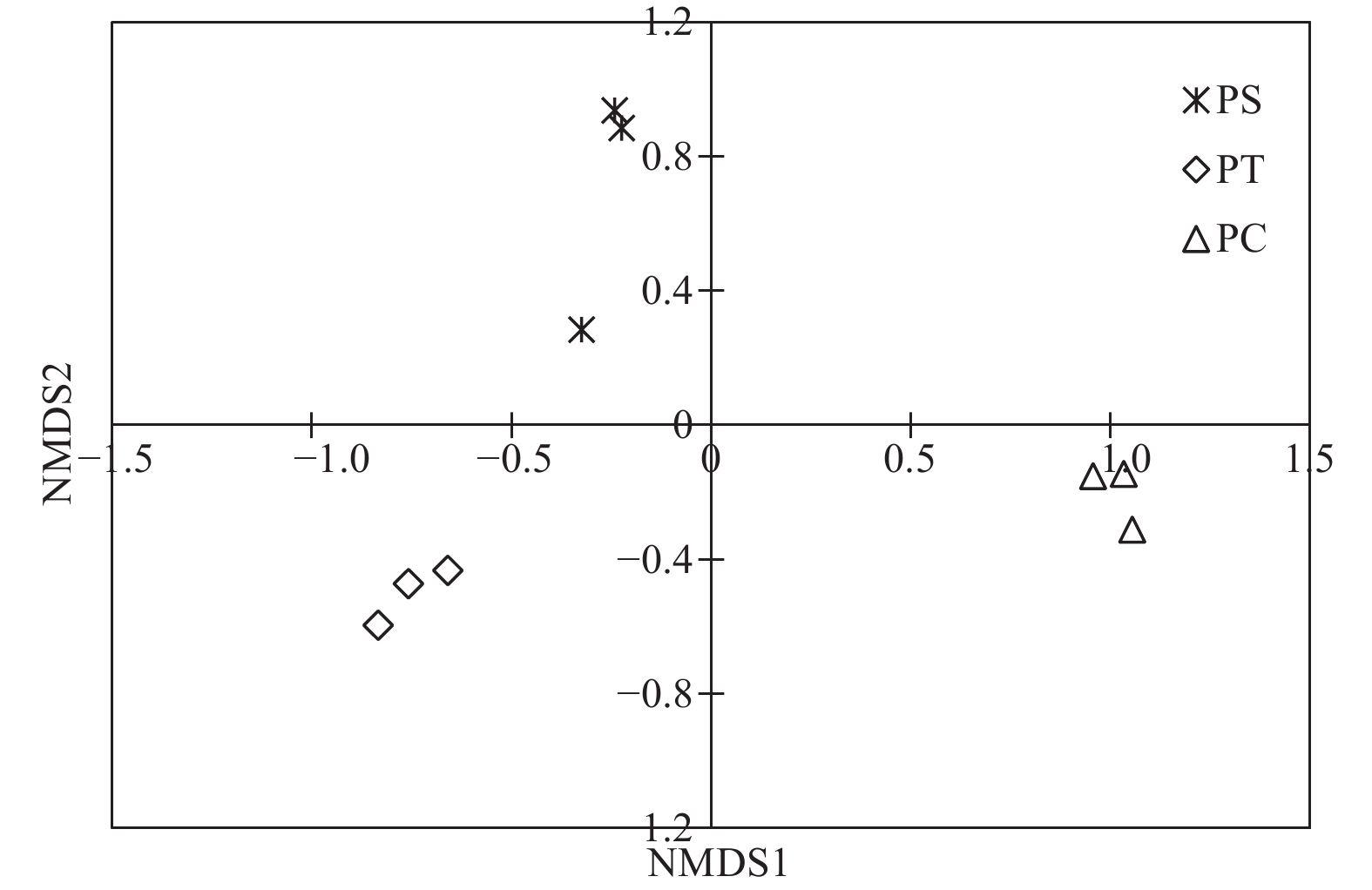

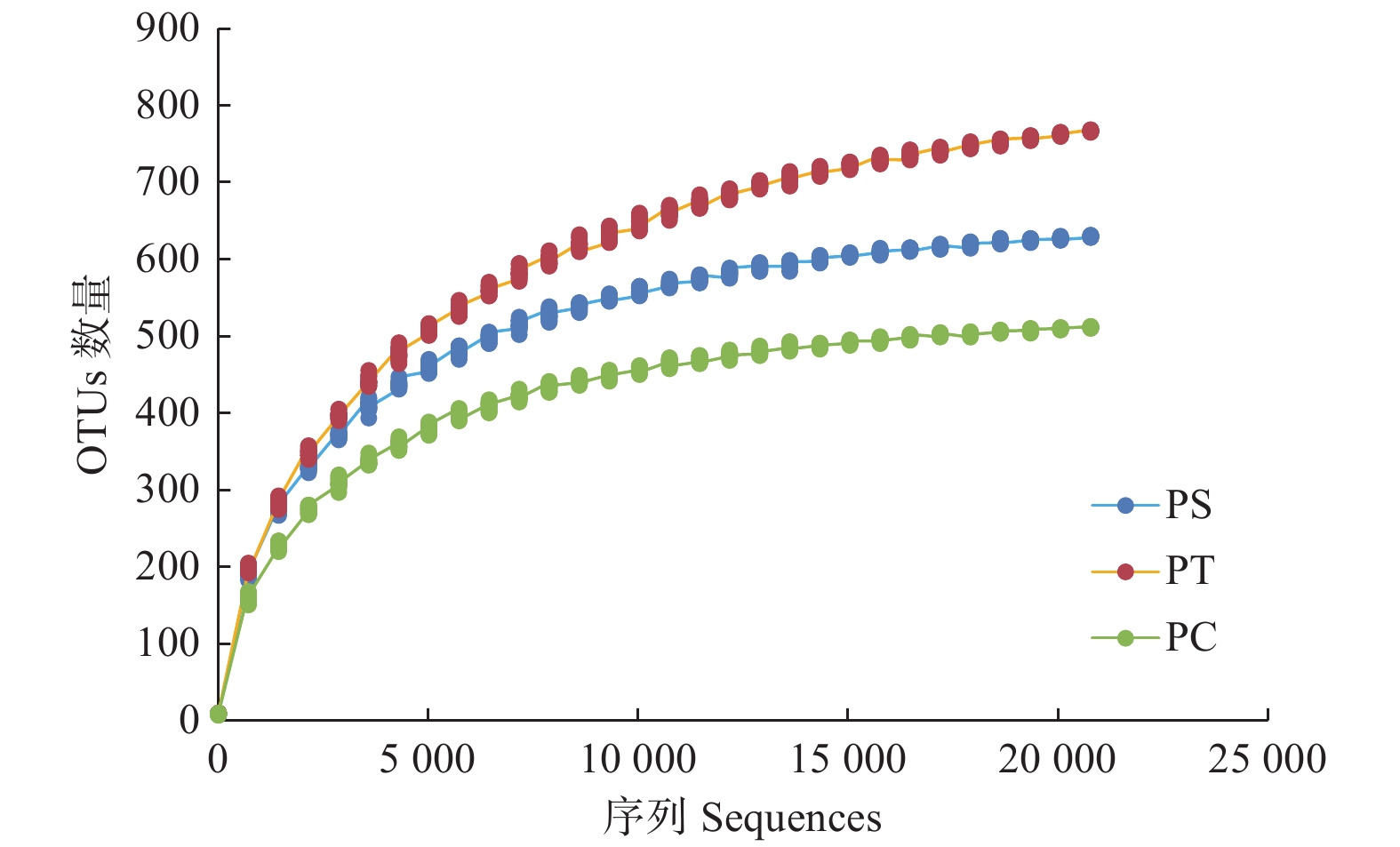

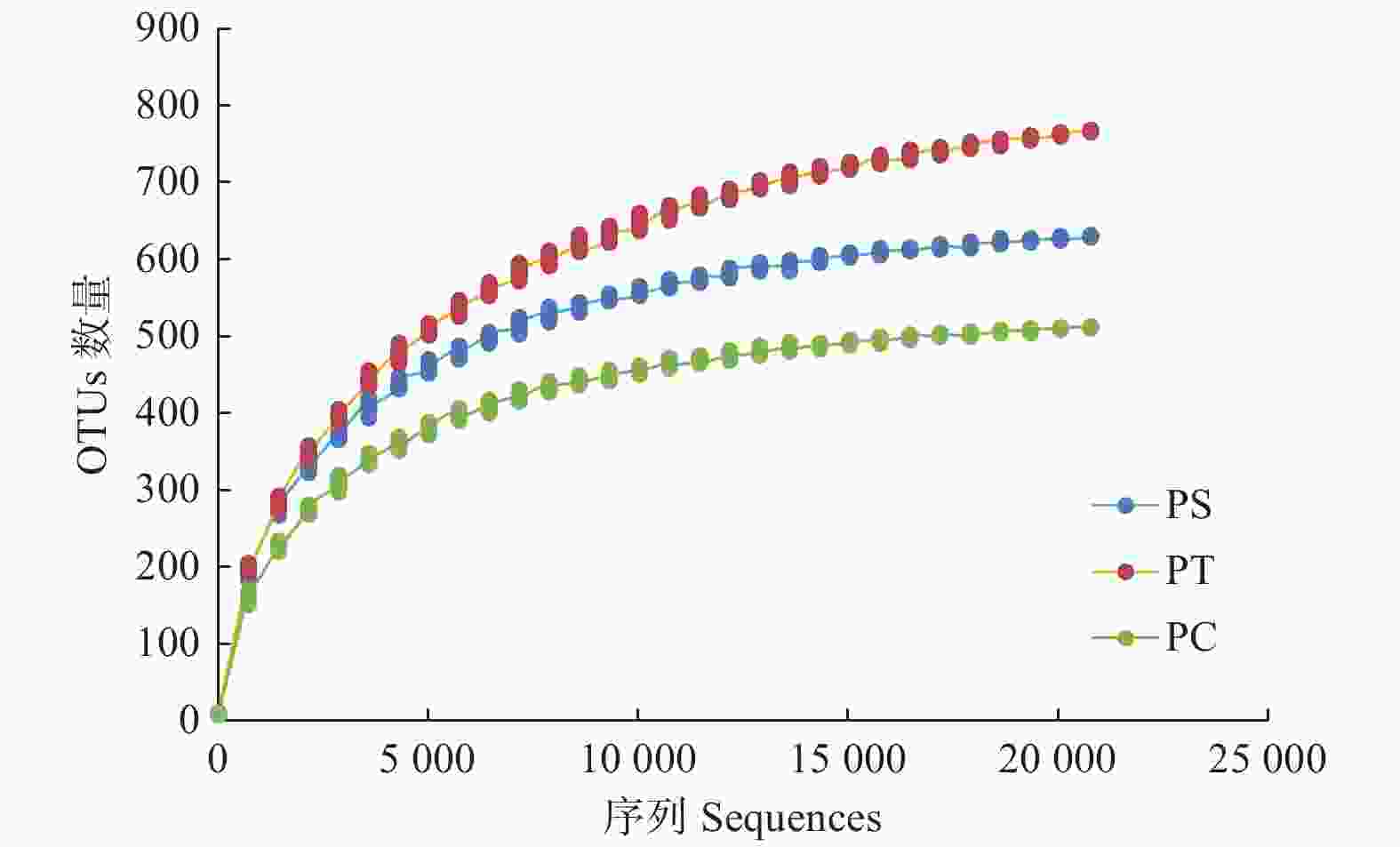

通过对9个样地的土壤样品DNA测序分析,以97%相似性阀值进行OTU聚类,获得真菌群落结构组成信息。真菌测序深度(Coverage)为97%,与数据库进行比对后可知,真菌包括15个门、54个纲和513个属。测序结果经去除嵌合体和低质量的序列后,从所有样品中共得到真菌ITS序列494,675条,平均每个土壤样品有54 963条序列,平均长度为330 bp。为了确定样品的稀疏曲线,从每个样本中随机选择21 490个reads,在3%差异水平下,随着实测序列数量的增加,曲线趋于平坦,表明本试验获得了大部分样本信息,能够反映不同人工林土壤真菌群落组成(图1)。当序列相似度为97%时,在真菌门水平上,樟子松人工林、油松人工林和杨树人工林分别有579、464和708个OTU(表3)。基于Unweighted UniFrac距离的NMDS分析结果,发现樟子松人工林和油松人工林土壤真菌群落结构具有较大的相似性,都位于NMDS1轴的负半轴,而杨树人工林真菌群落位于NMDS1轴的正半轴,与樟子松和油松人工林土壤真菌群落明显沿NMDS1轴分开(图2)。

Figure 2. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis based on Unweighted UniFrac distance under different plantation forests

树种

Tree speciesOTUs Simpson指数

Simpson indexChao 1指数

Chao1 indexACE指数

ACE indexShannon指数

Shannon index樟子松人工林

Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica579 0.962±0.018abAB 617.97±40.91bB 622.58±49.00bB 6.60±0.66aA 油松人工林

Pinus tabuliformis464 0.942±0.004bB 472.46±57.46cC 471.26±56.13cC 6.14±0.51aA 杨树人工林

Populus ×canadensis708 0.980±0.003aA 905.96±33.74aA 931.47±38.63aA 6.73±0.77aA 注:表中数据为均值±标准差(n=3),不同小写字母表示不同处理之间差异显著(P<0.05),不同大写字母表示不同处理之间差异显著(P<0.01)。 Table 3. Soil fungal diversity index in different plantation forests

通过分析发现,付家林场不同人工林土壤真菌群落多样性指数存在显著差异,杨树人工林土壤真菌的Simpson指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数分别为0.980、905.96和931.47,都显著高于其他(P < 0.05);油松人工林最低,分别为0.942、472.46和471.26。不同人工林土壤真菌的Shannon指数无显著差异(表3)。土壤pH值与ACE指数(r = 0.81,P < 0.01)和Chao1指数(r = 0.81,P < 0.01)呈极显著正相关;土壤DOC与土壤真菌Simpson指数(r = 0.86,P < 0.01),ACE指数(r = 0.79,P < 0.05)和Chao1指数(r = 0.78,P < 0.05)呈显著正相关。土壤AP与土壤真菌ACE指数(r = 0.86,P < 0.01)和Chao1指数(r = 0.86,P < 0.01)呈极显著正相关,土壤C/N与土壤真菌Simpson指数(r = −0.80,P<0.01),ACE(r = −0.91,P<0.01)和Chao1指数(r = −0.91,P < 0.01)呈极显著负相关(图3)。

-

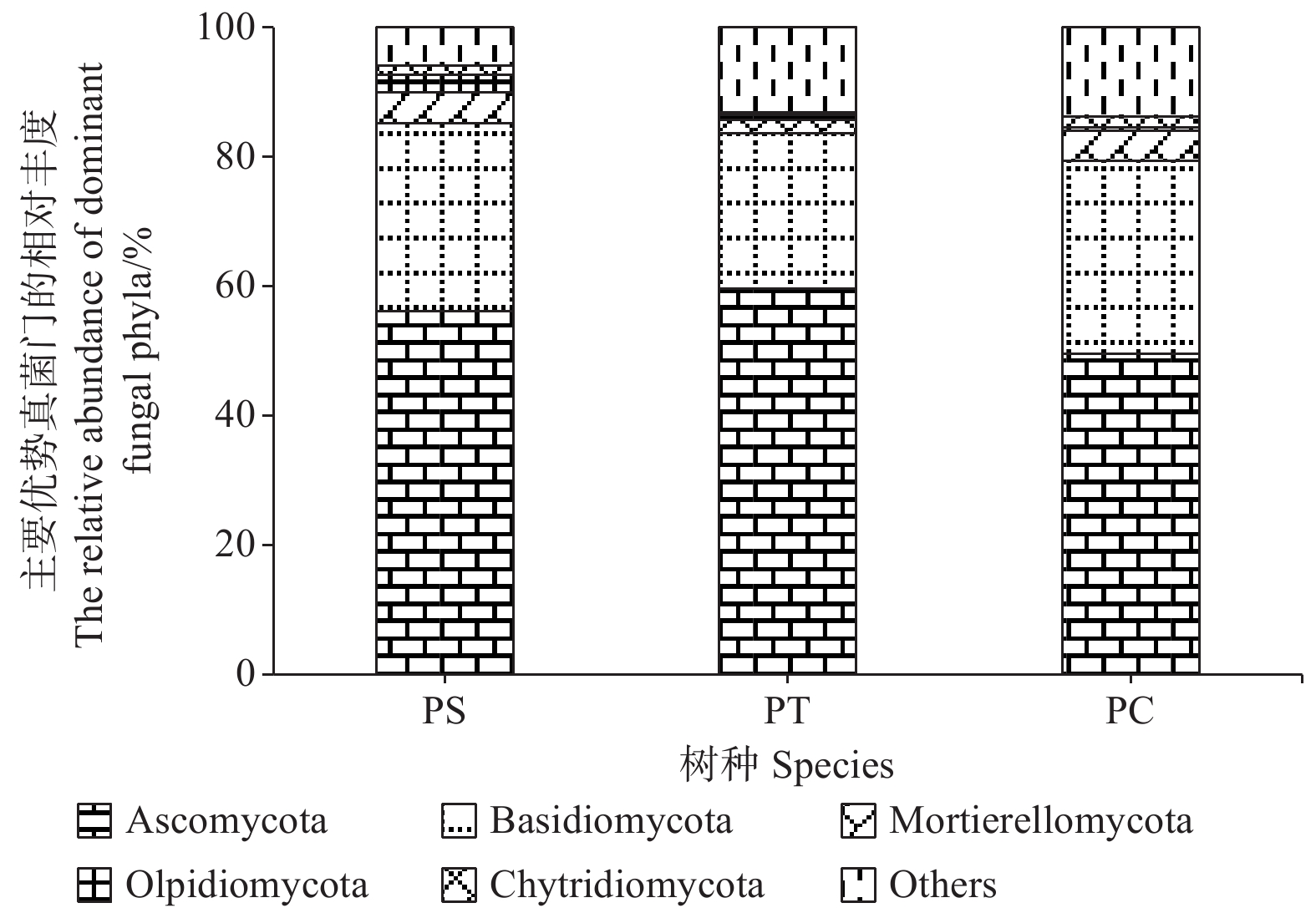

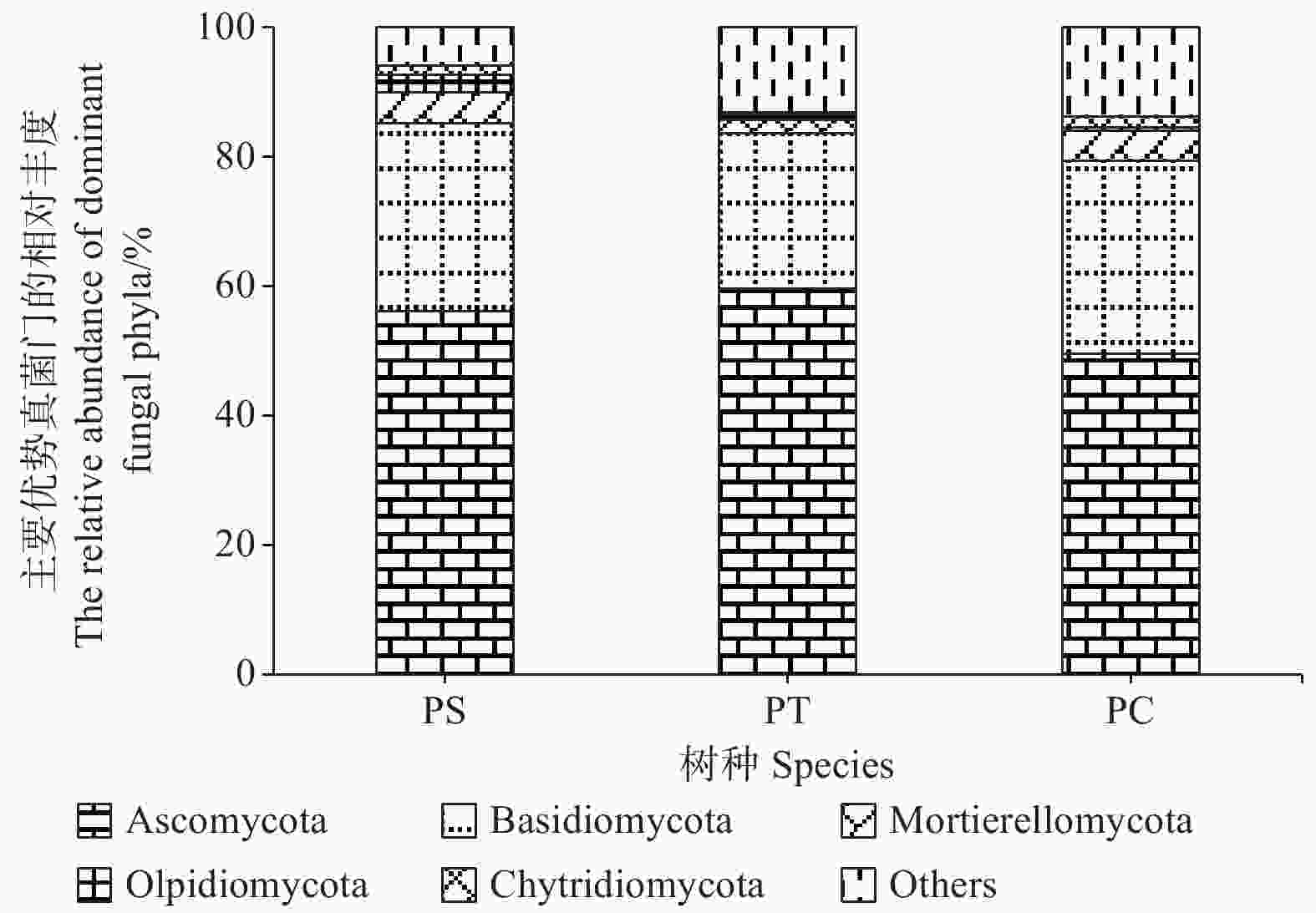

研究发现,付家林场不同样地土壤真菌群落组成存在差异,根据真菌的高级分类可知[28],所得序列属于14门(不包括unidentified),优势菌门为子囊菌门(Ascomycota)和担子菌门(Basidiomycota),它们的相对丰度分别为49.58% ~ 59.56%和23.99% ~ 29.77%。其他相对丰度占1%以上的门分别为被孢霉门(Mortierellomycota) (3.89%)、油壶菌门(Olpidiomycota)(1.28%)和壶菌门(Chytridiomycota)(1.21%)。油松人工林中子囊菌门的相对丰度最高,而油松人工林土壤中担子菌门、被孢霉门和壶菌门的相对丰度均最低(图4)。

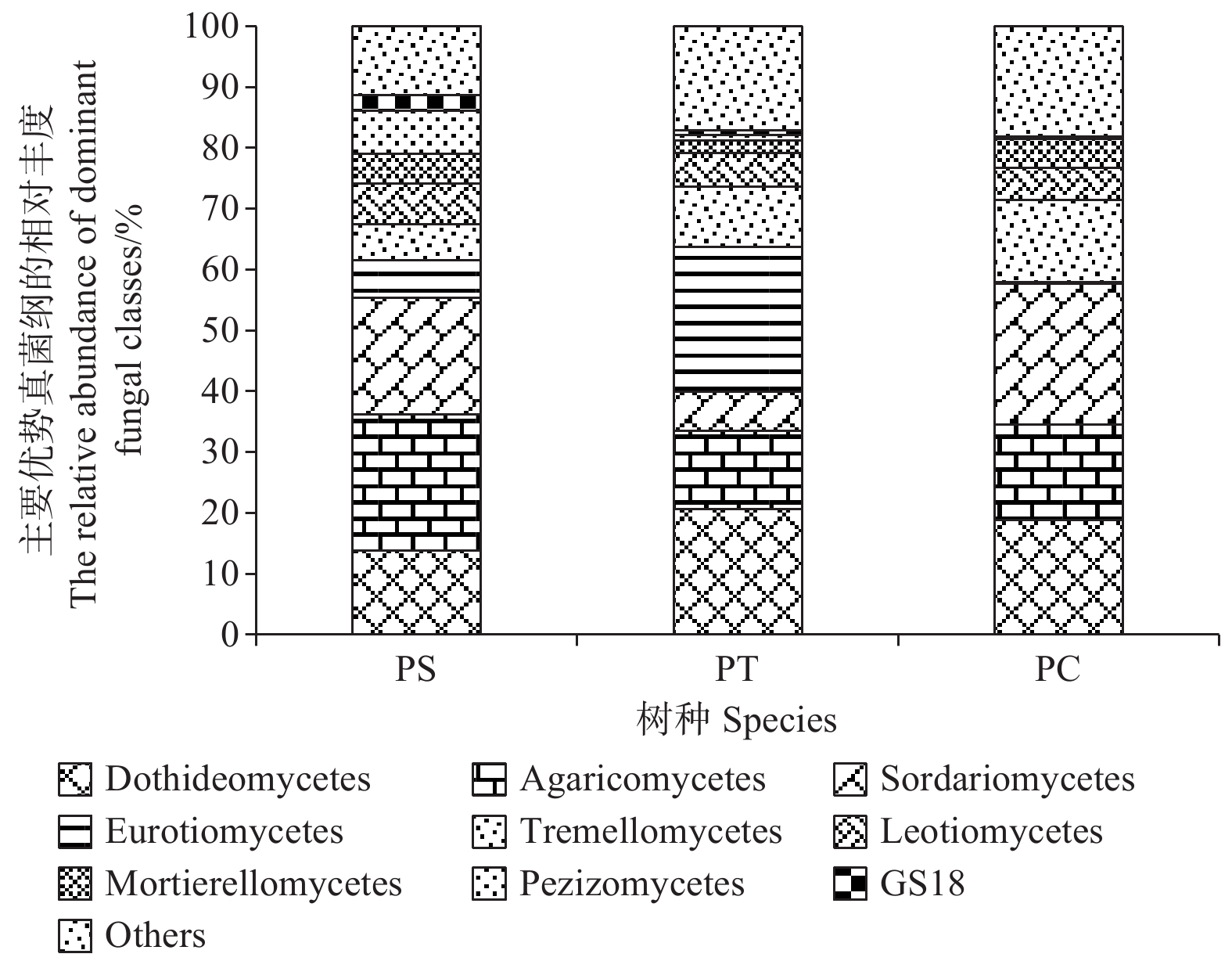

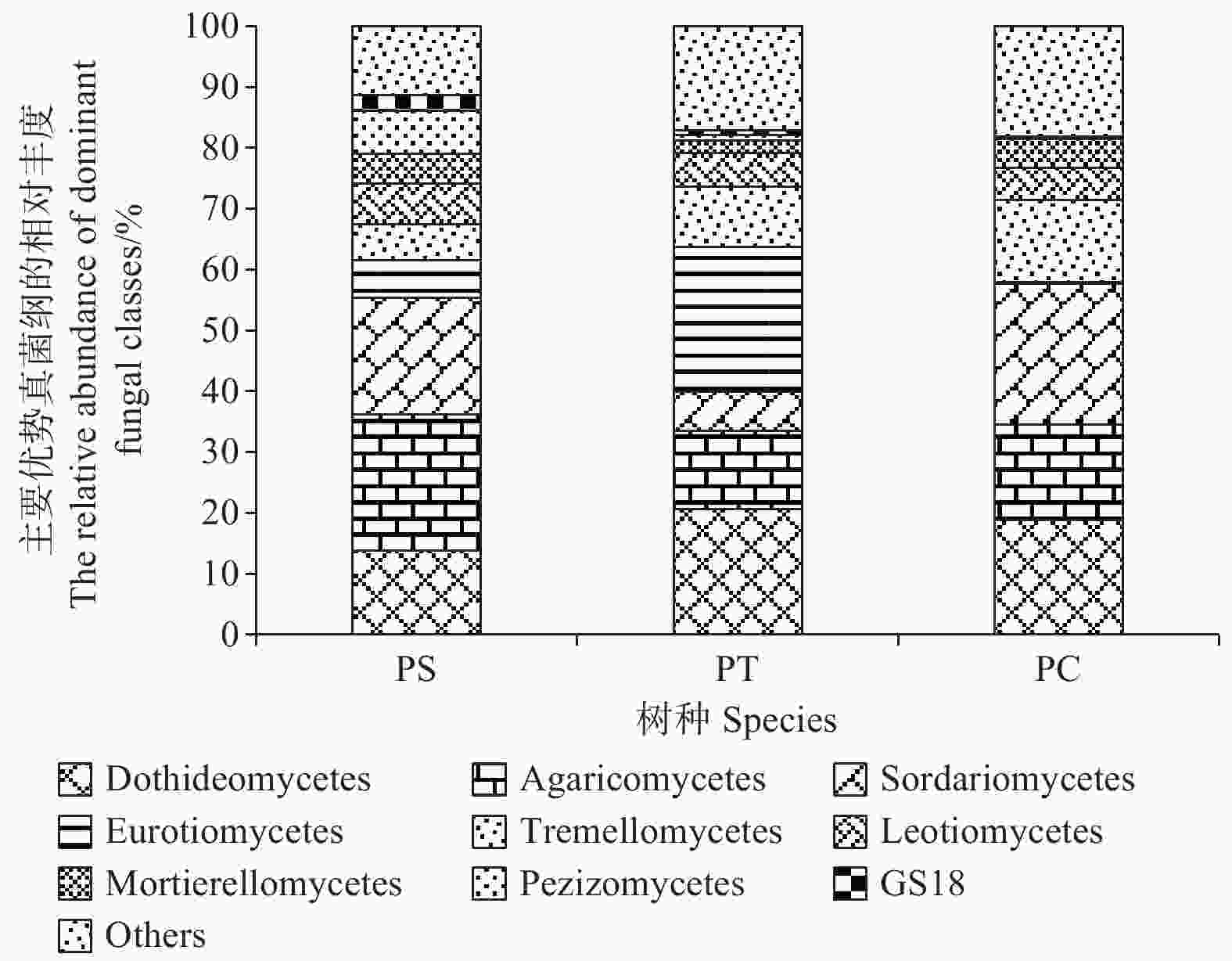

在纲水平上,平均相对丰度大于1%的纲共有9个,分别为座囊菌纲(Dothideomycetes)(13.86%~20.68%)、伞菌纲(Agaricomycetes)(12.83%~22.28%)、粪壳菌纲(Sordariomycetes) (6.38%~23.09%)、散囊菌纲(Eurotiomycetes) (0.26%~23.80%)、银耳纲(Tremellomycetes)(5.93%~13.55%)、锤舌菌纲(Leotiomycetes) (5.44% ~6.68%)、被孢霉纲(Mortierellomycetes) (2.13%~4.83%)、盘菌纲(Pezizomycetes)(0.22%~7.06%)和GS18 (0.17% ~2.58%)。其中,座囊菌纲、伞菌纲、锤舌菌纲、被孢霉纲和盘菌纲的相对丰度在不同人工林样地中无显著差异。在杨树人工林土壤中粪壳菌纲和银耳纲的相对丰度最高,且显著高于其他人工林样地(P<0.05),然而,在油松人工林土壤中散囊菌纲相对丰度含量最高,显著高于其他样地(P<0.05) (图5)。

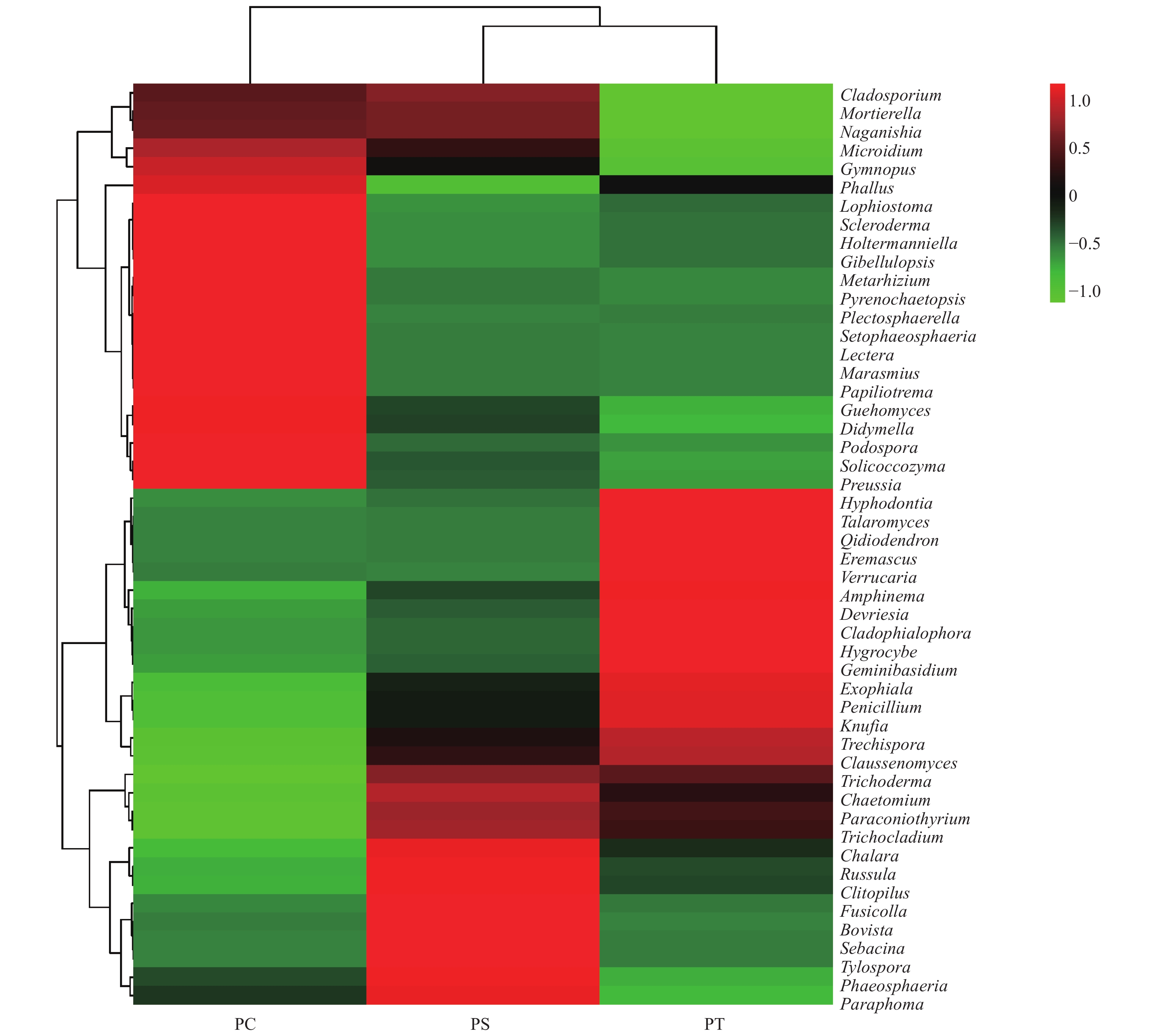

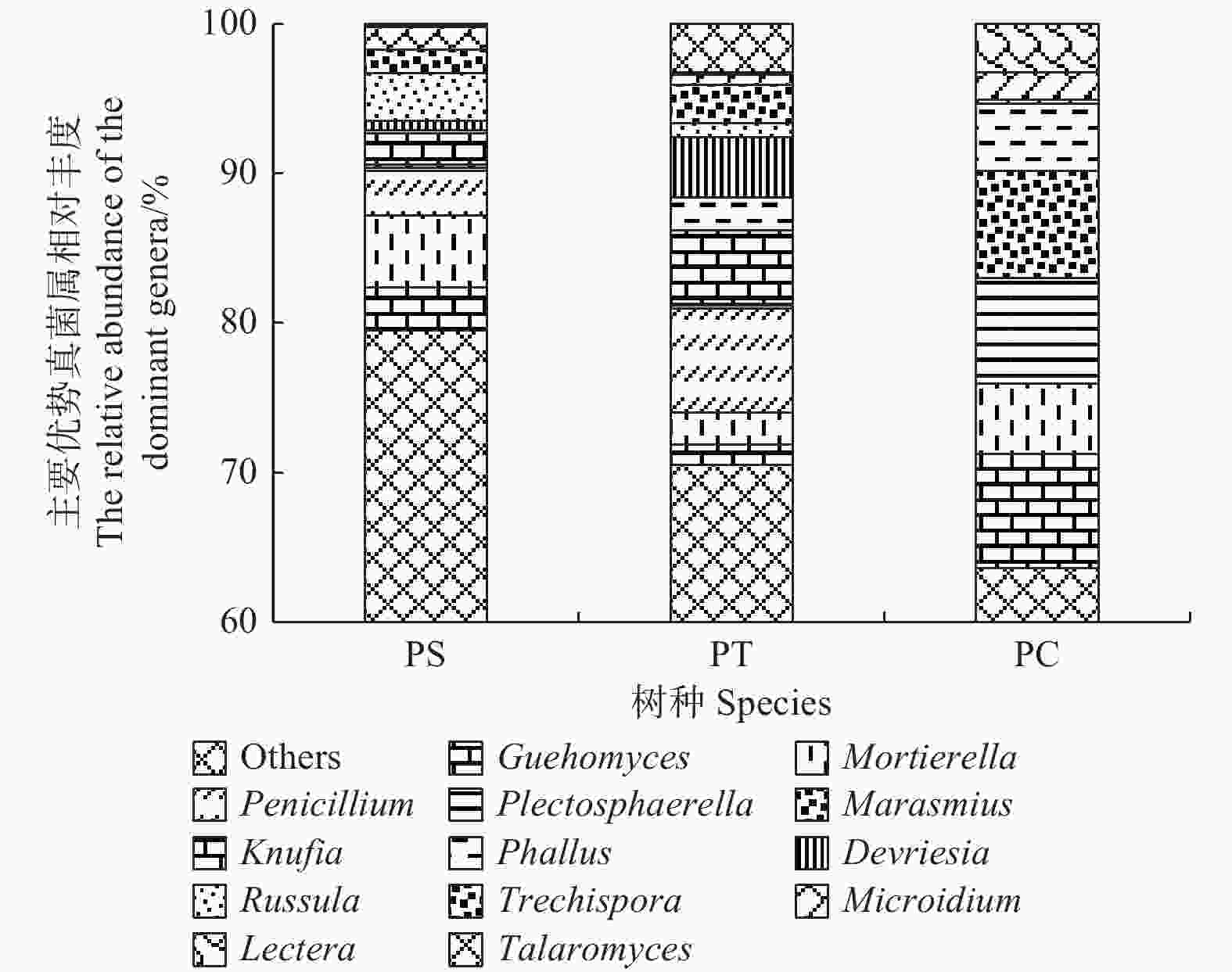

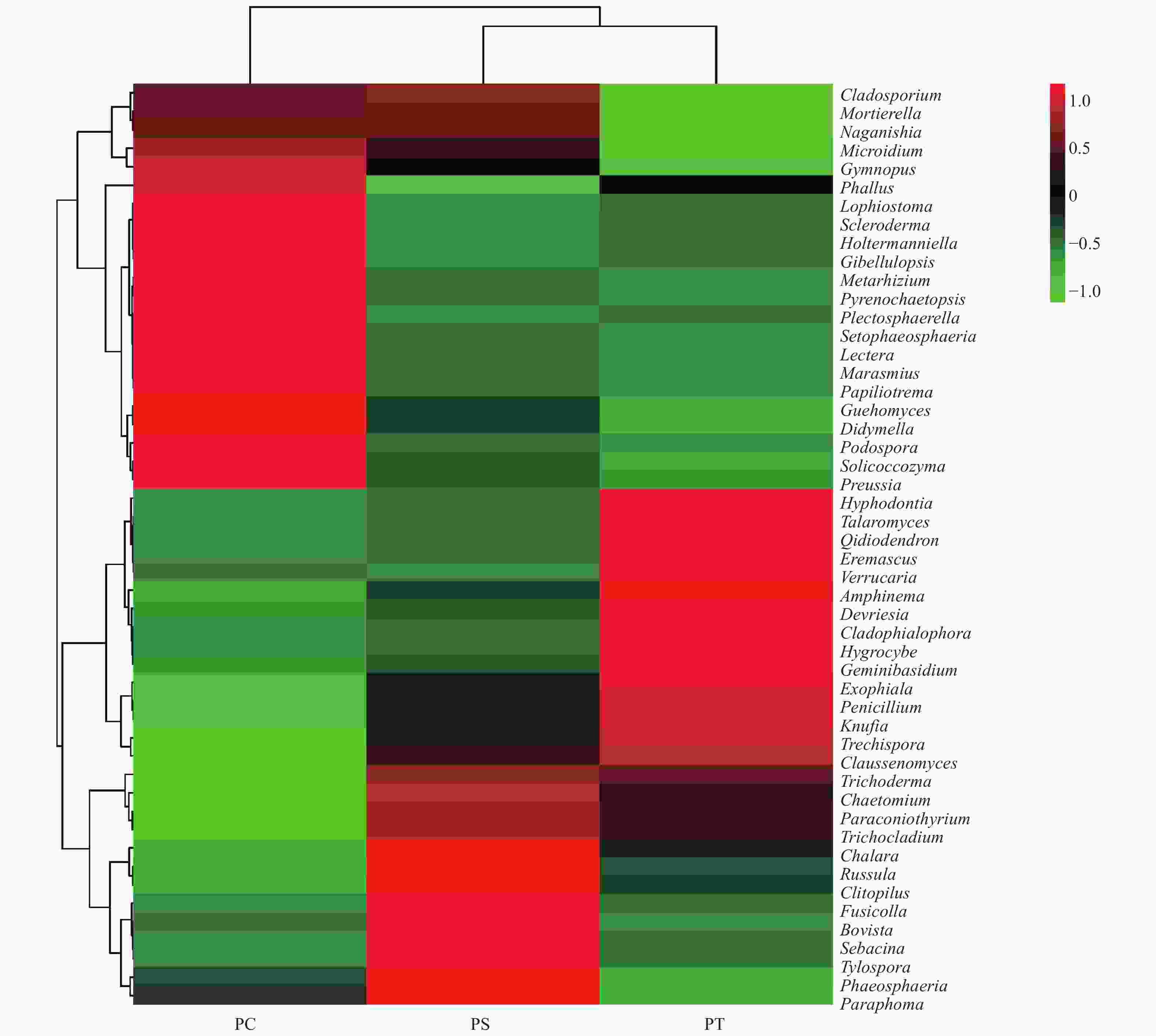

在所有的样品中共检测出513个属,其中,相对丰度大于1%的主要的真菌类群为Guehomyces (3.96%)、被孢霉属(Mortierella) (3.88%)、青霉菌属(Penicillium) (3.31%)、Plectosphaerella (2.52%)、小皮伞属(Marasmius) (2.50%)、Knufia (2.33%)、Phallus (2.31%)、Devriesia (1.54%)、红菇属(Russula) (1.48%),Trechispora (1.37%)、Microidium (1.35%)、Lectera (1.17%)和篮状菌属(Talaromyces)(1.10%)(图6)。相对丰度前50的真菌属的热图分析表明,不同植被类型的真菌群落结构不同,可以划分为两个类群,其中樟子松人工林和油松人工林为一类,杨树人工林为单独一类(图7)。

-

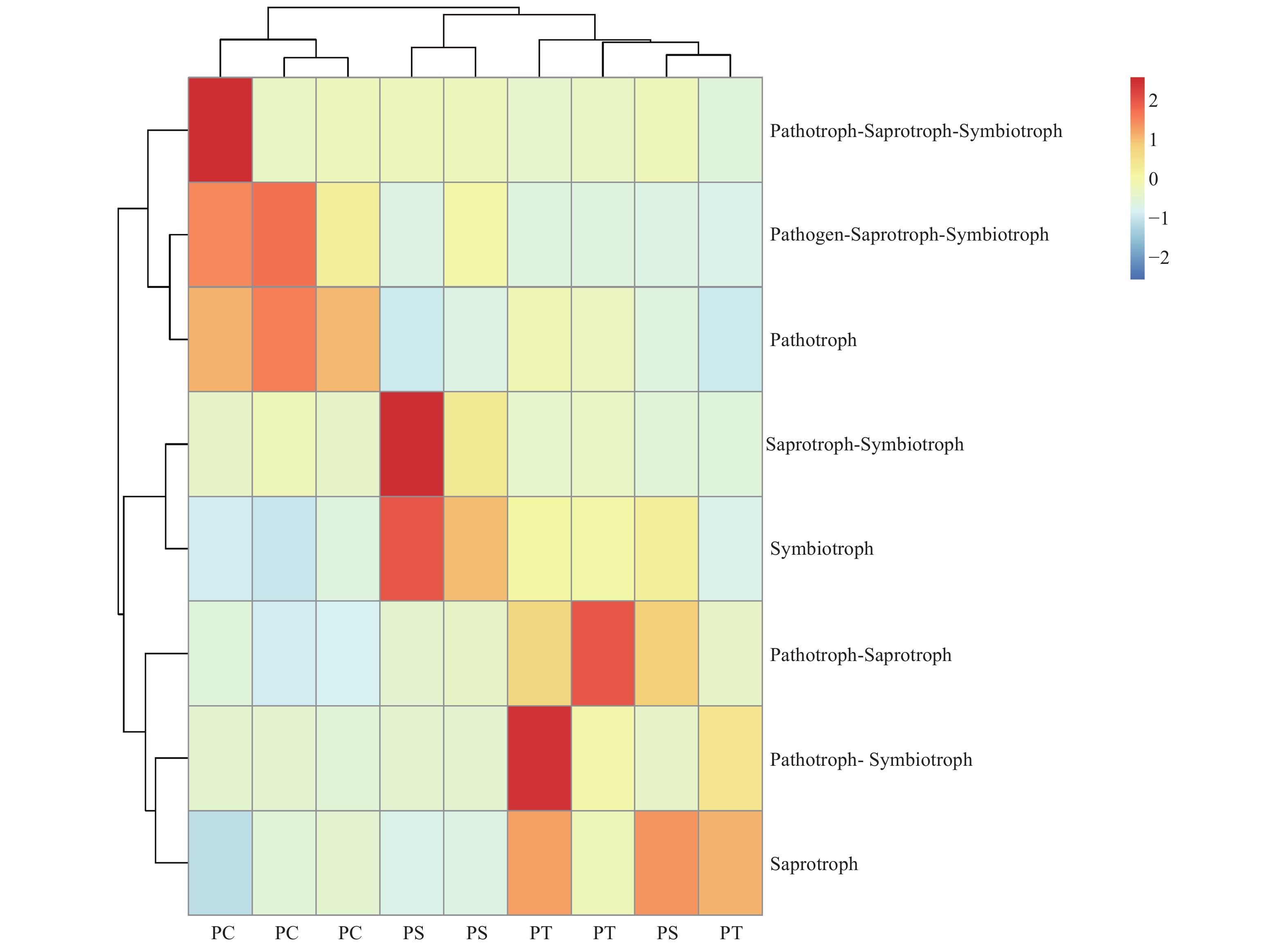

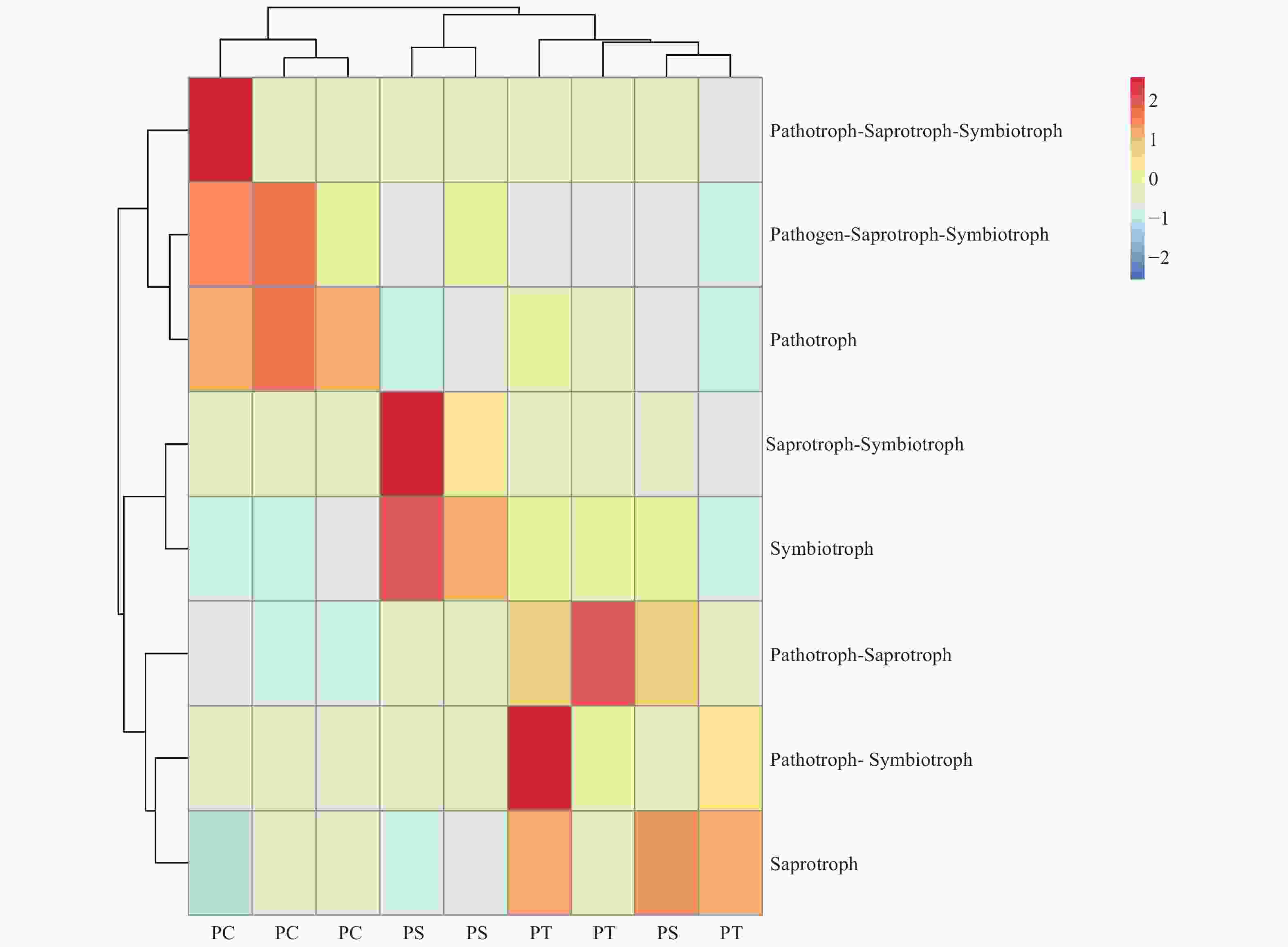

真菌的生态功能类群是基于营养型来划分的。根据FUNGuild数据库的比对结果,对3种人工林真菌的营养型(trophic mode)进行分类统计,结果如图3所示,检测到8个营养型(Trophic mode),分别为致病菌-腐生-共生营养型(Pathogen-Saprotroph-Symbiotroph)、病理营养型(Pathotroph)、病理-腐生营养型(Pathotroph-Saprotroph)、病理-腐生-共生营养型(Pathotroph-Saprotroph-Symbiotroph)、病理-共生营养型(Pathotroph-Symbiotroph)、腐生营养型(Saprotroph)、腐生-共生营养型(Saprotroph-Symbiotroph)和共生营养型(Symbiotroph)。该区3种人工林土壤真菌主要以腐生营养型为主,腐生-共生营养型次之。对不同人工林土壤真菌功能类群进行聚类分析结果表明,不同人工林真菌群落功能可划分为两个类群,其中油松人工林和红松人工林土壤真菌群落功能为一类,杨树人工林土壤真菌功能类群为一类(图8)。

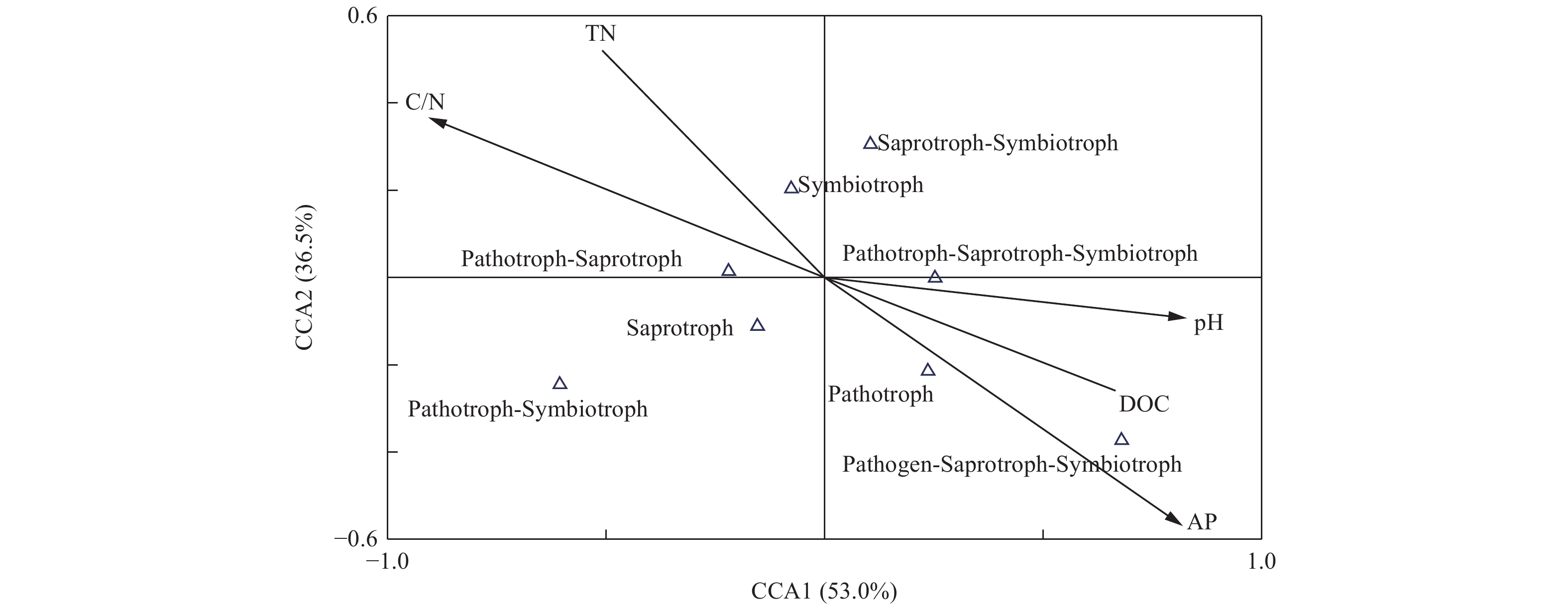

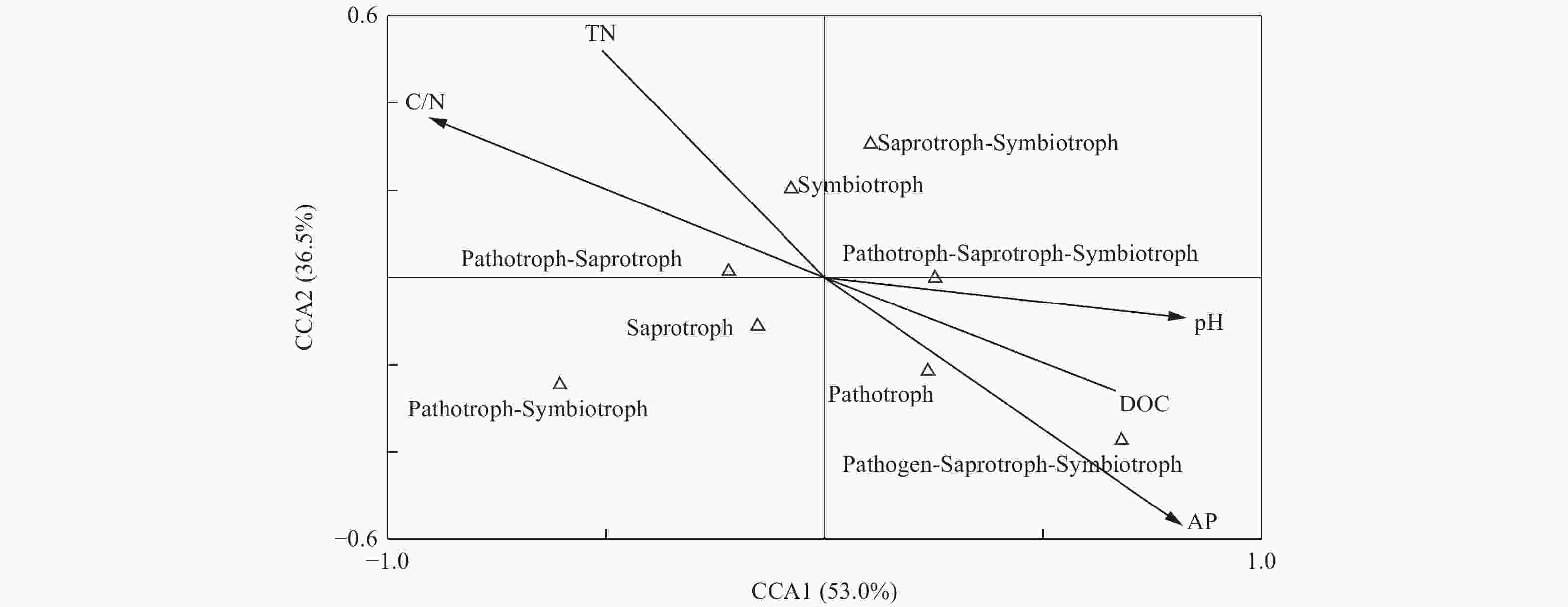

为研究土壤真菌群落功能与土壤环境因子间的相关性,采用CCA分析对土壤环境因子和真菌群落功能类的关系进行限制性排序分析,如图9所示,土壤pH (r=0.76)、可溶性有机碳(r=0.61)、C/N (r=−0.83)和速效磷(r=−0.75)与CCA1轴的相关性较大,第一轴的解释量为53.0%。土壤速效磷(r=−0.54)与第二轴的相关性较大,解释量为36.5%。由此可见,土壤pH、可溶性有机碳、C/N和速效磷为土壤真菌群落功能的主要影响因子。

3.1. 不同人工林土壤特性

3.2. 不同人工林土壤真菌多样性特性

3.3. 不同人工林土壤真菌群落结构特征

3.4. 不同人工林土壤真菌群落功能比较

-

不同人工防护林会显著改变土壤化学特性。与樟子松和油松人工林相比,杨树人工林土壤pH值最高(表1)。Yoshimura等人[29]研究发现,松树林土壤pH值均较橡树和桦树林土壤低,这主要是由于针叶林凋落物含有较高的酸性物质[30]。不同森林类型土壤C/N差异显著[31],本研究发现人工林土壤C/N依次为油松>樟子松>杨树,与以往的研究结果类似[29]。凋落物是人工林生态系统养分归还的重要组成部分,在很大程度上影响着土壤有机质的形成[32],与针叶树樟子松和油松相比,杨树能更好地提高土壤可溶性有机碳和速效磷的含量,这可能是由于不同树种向土壤输入的凋落物的质量和数量不同所致[33],在相同生境中,阔叶树种枯落物分解速率大于针叶树种[34],与杨树相比,樟子松和油松凋落物分解慢,养分释放需要时间较长,归还量较少,从而造成针叶人工林土壤中的速效养分的含量较低。由此可见,在同一气候条件下,人工林树种对土壤特性存在显著影响,尤其是在阔叶林和针叶林之间。

-

本研究发现,不同人工林土壤真菌在门、纲和属的组成上具有一定的相似性,但是,不同人工林土壤真菌在门、纲和属的相对丰度上存在一定差异。众所周知,土壤微生物所利用的碳源主要来自于植物凋落物及根系分泌物,凋落物的丰富程度和品质高低直接决定微生物的数量及群落结构[35],由于不同的植被类型具有不同的凋落物残体和根系分泌物,所以使不同人工林土壤微生物的群落多样性和结构存在差异[36-38]。本研究发现,在付家林场3种人工林土壤中,子囊菌门真菌为优势菌门,担子菌门次之,研究结果与湖南杉木人工林[39]、老挝热带草地[40]、关帝山森林土壤[41]、以及宁南山区人工林草[42]土壤中优势真菌门类群相一致。Curlevski等人[43]的研究也表明,澳大利亚亚热带森林土壤中的子囊菌门真菌群落多于担子菌门。然而,有研究发现中国亚热带森林土壤的真菌群落主要以担子菌门为主[44]。担子菌和子囊菌均喜欢通气好的土壤条件[45],它们属于陆生菌物,是土壤有机质的主要分解者[46]。在森林土壤中,多数子囊菌为腐生菌,能够分解角质素和木质素等许多较难降解的有机物质,在养分循环中扮演着重要作用[47],它们通常在偏酸性土壤中大量存在。本研究发现,在pH值最低的油松人工林土壤中,子囊菌门相对丰度最高。Heatmap和NMDS分析结果表明,不同人工林土壤真菌群落存在明显差异,尤其针叶林与阔叶林之间的差异更大。本研究结果与He等人的研究结果相类似[48],均表明人工林树种不同,其土壤真菌群落组成也不同[49]。

-

土壤真菌多样性是土壤质量变化的敏感指标,能够反映真菌群落总体的动态变化[50]。本研究结果表明,不同人工林土壤真菌多样性具有显著差异,Myers等人[51]也得到相似的结果。其中,杨树人工林土壤真菌的Simpson指数、Shannon指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数均高于樟子松和油松人工林,表明杨树人工林土壤具有较高的真菌多样性和均匀性,这主要是由于樟子松和油松均属针叶林,针叶林枯枝落叶在分解过程中产生酸性物质[52],使土壤酸性增强,且针叶树凋落物分解慢,养分归还少[53],微生物活性和多样性受到限制。可见,植被类型不仅影响土壤养分特征,也显著影响土壤微生物群落多样性[54]。除此之外,森林生态系统中土壤真菌多样性还受多种土壤环境因子的影响[55],其中,土壤酸碱度也是影响土壤微生物群落结构的重要环境因子[56],土壤中碳、氮、磷等元素的含量也影响并制约着土壤中各类微生物群落的活性[57],多样性及其组成[58-59]。本研究结果表明,土壤pH值与真菌ACE指数和Chao1指数呈极显著正相关,与关帝山森林土壤真菌群落结构的研究结果相一致[40]。真菌群落对土壤pH适应范围较宽,pH在5~9之间的土壤均不会抑制真菌的生长[60]。本研究结果表明土壤的DOC、AP和C/N也对真菌的多样性和真菌群落功能具有显著影响,可能是由于不同植物物种会通过改变土壤结构和营养状况从而间接地改变真菌的生存环境,影响土壤真菌群落多样性以及功能特征[61]。

4.1. 土壤环境因子对不同人工林的响应

4.2. 土壤真菌群落结构对不同人工林的响应

4.3. 土壤真菌群多样性与不同土壤环境因子间的相关性

-

杨树、樟子松和油松为辽西北风沙地区发挥生态效应的主要造林树种。本研究采用高通量测序与FUNGuild综合分析的方法,对辽西风沙区3种不同造林树种的土壤真菌群落多样性、真菌群落结构及其功能进行了研究,结果表明:(1)杨树人工林能显著增加土壤pH值、土壤可溶性有机碳和速效磷的含量,降低土壤的C/N;(2)杨树人工林能够提高土壤微生物的多样性,且土壤pH、可溶性有机碳、速效磷和C/N是影响该区真菌多样性和真菌群落功能的主要因素;(3)3种人工林样地中共有5个真菌门和13个优势真菌属,其中,相对丰度最大的为子囊菌门和担子菌门;(4)Heatmap和NMDS分析结果表明不同人工林土壤真菌群落结构和功能具有一定差异,且在阔叶林和针叶林之间差异较大。试验结果为辽西北风沙地区不同针阔树种造林土壤养分及土壤微生物的研究等提供数据支持,也为该地区土壤改善、生态环境治理和树种选择提供科学依据。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: