-

落叶松八齿小蠹(Ips subelongatus Motschulsky)为鞘翅目、小蠹亚科、齿小蠹属昆虫,在东亚广泛分布,是中国北方3种落叶松(兴安落叶松、华北落叶松和长白落叶松)的次期性严重为害的蛀干害虫[1],在种群暴发期可为害健康树木。作为影响本土针叶树并对非本土针叶树有威胁的主要害虫,该害虫于2003年被中国列入“全国林业危险性有害生物名单”(国家林业局,2003年),于2005年被欧洲地中海植物保护组织列入A2预警名单(EPPO,2005)。此外,小蠹虫携带的多种病原微生物,特别是长喙壳真菌,在小蠹虫为害过程中会加重对树木的危害[2]。

长喙壳真菌是一类包括蛇口壳目(Ophiostomatales)真菌及相似类群真菌的总称,其中一些种类是引起林木病害的重要病原菌,如引起榆树荷兰病的Ophiostoma ulmi和Ophiostoma novo-ulmi、引起月桂枯萎病的Raffaelea lauricola及引起针叶树黑根病的Leptographium wageneri[2-4]。已有研究证实,齿小蠹伴生真菌群落中的先锋种Endoconidiophora spp.,如Endoconidiophora fujiensis,对日本地区的落叶松毒力较强,可引发寄主坏死,或诱导寄主落叶松产生强烈的抗性反应[5]。Endoconidiophora polonica高密度接种在挪威云杉上,能导致其死亡[6]。

小蠹虫和长喙壳真菌在长期的协同进化过程中形成了复杂的伴生关系,二者之间的联系在小蠹虫定殖寄主过程中起着重要作用[7-8]。研究表明,长喙壳真菌可以合成小蠹虫生长发育所必需的甾醇[9]、解毒寄主树木的防御物质[10-12]、释放化学信息素吸引或排斥同种小蠹虫[13-14]等。然而,一些寄主萜类化合物对小蠹虫及其伴生真菌具有毒性,如针叶树在受到小蠹虫攻击时会增加单萜类化合物的合成,以抵抗小蠹虫的入侵,当萜类物质浓度高于小蠹虫的生理耐受阈值时,抑制小蠹虫的攻击[15];离体试验也表明,在培养基中添加α-pinene和limonene等单萜类物质,可抑制长喙壳真菌的生长[14, 16]。

研究明确小蠹虫传播的真菌是否会引起植物病害以及植物是否会对小蠹虫及其伴生真菌产生抗性,是关于小蠹虫传播病菌的2个关键科学问题。本研究将2010—2018年采集分离的12种落叶松八齿小蠹伴生长喙壳真菌代表性菌株接种到5年生落叶松苗上[17],观察不同真菌或菌株之间的致病力是否存在差异,并分析寄主防御相关代谢物质的变化,以探究落叶松八齿小蠹及其伴生长喙壳真菌复合物对落叶松的潜在风险。

-

本试验选用的12种长喙壳真菌为由2010—2018年采集的落叶松八齿小蠹虫体和坑道中分离纯化得到的菌株[17],分别为E. fujiensis、E. laricicola、Ophiostoma hongxingense、Ophiostoma peniculi、Ophiostoma pseudobicolor、Ophiostoma subelongati、Ophiostoma genhense、Ophiostoma lotiforme、Ophiostoma rufum、Ophiostoma minus、Ophiostoma multisynnematum和Ophiostoma xinganense,每种真菌各选用2个菌株用于致病力试验(表1)。

种名

Species菌株号

Strain No.寄主

Host采集地

LocationEndoconidiophora fujiensis MJG55 日本落叶松 Larix kaempferi 辽宁抚顺 Fushun, Liaoning MJG29 日本落叶松 L. kaempferi 辽宁抚顺 Fushun, Liaoning E. laricicola TRL63 西伯利亚落叶松 L. sibirica 新疆阿勒泰 Altay, Xinjiang KBLK9 西伯利亚落叶松 L. sibirica 新疆阿勒泰 Altay, Xinjiang Ophiostoma hongxingense HXS70 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 黑龙江哈尔滨 Harbin, Heilongjiang HXS72 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 黑龙江哈尔滨 Harbin, Heilongjiang O. peniculi CFCC52688 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia GH77 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia O. pseudobicolor CFCC52683 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52684 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古赤峰 Chifeng, Inner Mongolia O. subelongati CFCC52693 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 黑龙江哈尔滨 Harbin, Heilongjiang ZHS37 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 黑龙江哈尔滨 Harbin, Heilongjiang O. genhense CFCC52675 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52676 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia O. lotiforme CFCC52691 樟子松 Pinus sylvestris var. mongholica 内蒙古海拉尔 Hailar, Inner Mongolia CFCC52692 樟子松 P. sylvestris var. mongholica 内蒙古海拉尔 Hailar, Inner Mongolia O. rufum CFCC52681 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52682 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia O. minus CFCC52697 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52698 樟子松 P. sylvestris var. mongholica 内蒙古海拉尔 Hailar, Inner Mongolia O. multisynnematum CFCC52677 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52678 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia O. xinganense CFCC52679 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia CFCC52680 兴安落叶松 L. gmelinii 内蒙古呼伦贝尔 Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia Table 1. The information of tested strains

-

选择移栽于中国林科院内的5年生长白落叶松(Larix olgensis A. Henry)作为试验材料。这些落叶松高2.0~3.0 m,平均2.49 m,地径2.05~4.77 cm,平均3.05 cm。

-

菌株在2% MEA培养基上25 ℃黑暗条件下培养7 d,用经灭菌的直径6 mm软木塞打孔器在新培养菌落边缘打取菌苔。于2019年7月9日随机选择60棵落叶松,在离地30 cm处的树干上,用经灭菌的直径6 mm的软木塞打孔器打孔至木质部,用无菌牙签将菌苔接入接种孔,然后盖上树皮,用封口膜缠绕,并用胶带固定。以2% MEA培养基作为接种对照。每棵树上设1个接种点,每个处理各设5次重复。

-

接种60 d后,撕开接种点的胶带和封口膜,用壁纸刀刮去接种点周围病斑区域的外树皮,测量病斑的长和宽,并记录相关数据。

-

测量病斑大小后,每个处理随机选择3个重复,在接种植株病健交界处取约1 cm2样品放至15 mL无菌离心管并带回实验室,于−4 ℃冰箱保存。次日,样品表面经2%次氯酸钠消毒1 min,然后用无菌水冲洗3次,经无菌滤纸吸去表面水分后取约1 mm2组织碎片放置在2% MEA培养基上进行培养,根据菌落形态学和核酸β-微管蛋白(BT)基因片段序列比较鉴定是否为原始接种的长喙壳菌株。

-

对MJG55(E. fujiensis)和TRL63(E. laricicola)菌株和对照接种1、7、14、30和60 d后的5棵落叶松进行单萜类物质测定,以评估寄主防御反应强弱。用聚乙烯薄膜(48 cm × 60 cm,雷诺公司,美国)包裹接种点周围树干,用特氟龙管将含有100 mg Porapak-Q 吸附剂(默克公司,德国)的玻璃管连接在小型真空泵上形成闭环动态顶空采样系统,以500 mL·min−1的流速持续1 h收集寄主挥发性物质。将含有挥发物的玻璃管两端用锡纸包裹并缠绕封口膜,放入装有干冰的保温箱并带回实验室。用2 mL色谱级正己烷洗脱寄主挥发物,用温和的氮气将样品浓缩至50 μL,置于−20 ℃冰箱保存直至气相色谱检测。气相色谱分析方法同Liu等人描述[18]。将样品放置在配有火焰离子检测器和自动进样器的气相色谱仪(GC-FID,安捷伦,美国)上,使用口径0.25 mm × 0.2 μm,30 m长的HP-5色谱柱进行分析,每次进样1 μL。

-

根据Rajtar等[19]的方法,计算接种点病斑面积(长 × 宽)。单萜类化合物释放速率根据处理组和健康组的差值(Δ)进行分析。使用IBM SPSS Statistics19针对不同菌株产生的病斑、MJG55和TRL63菌株处理的落叶松在同一时间产生的单萜类化合物释放速率、MJG55或TRL63菌株处理在不同时间产生的单萜类化合物释放速率,进行单因素方差分析(LSD test,α=0.05)。

-

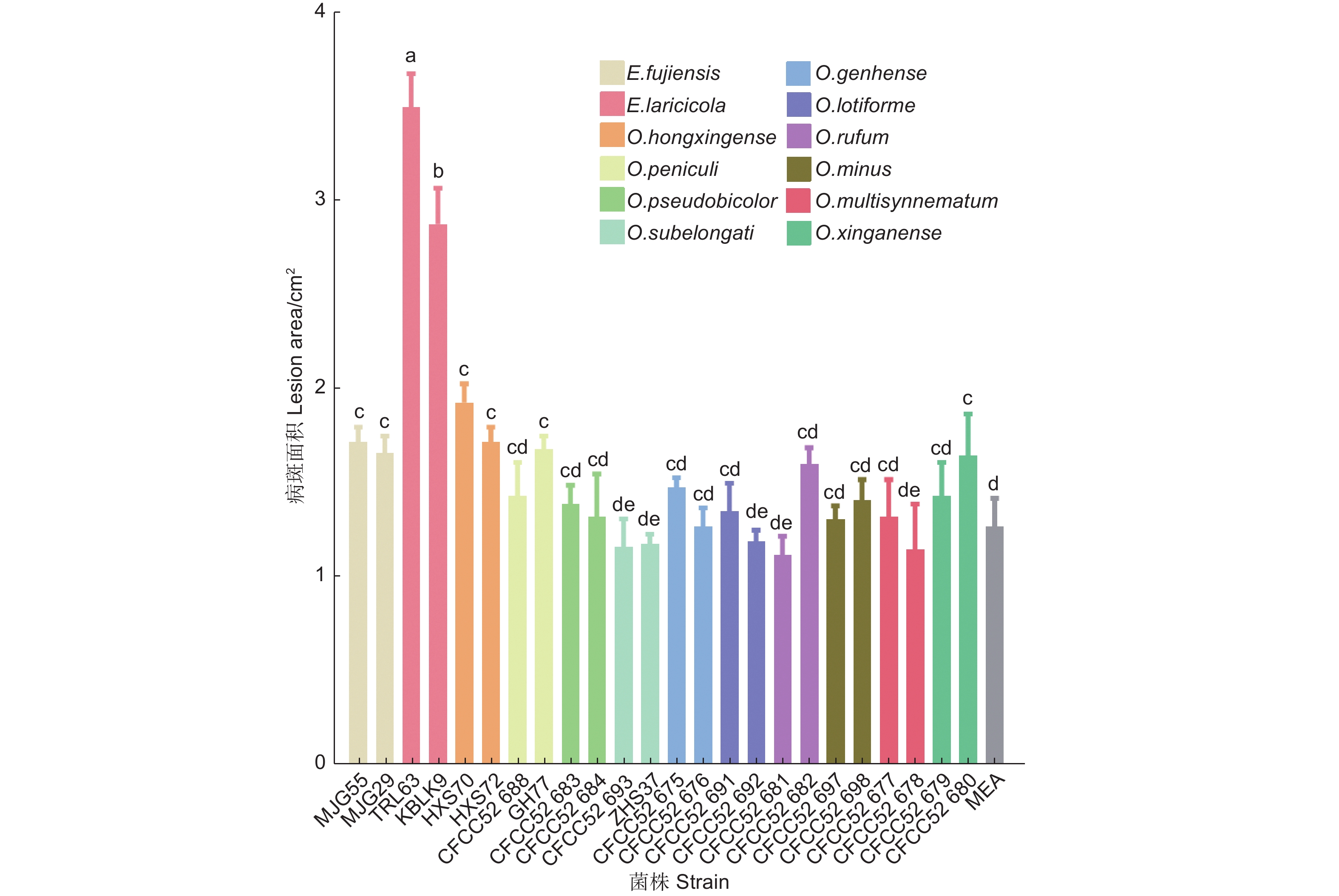

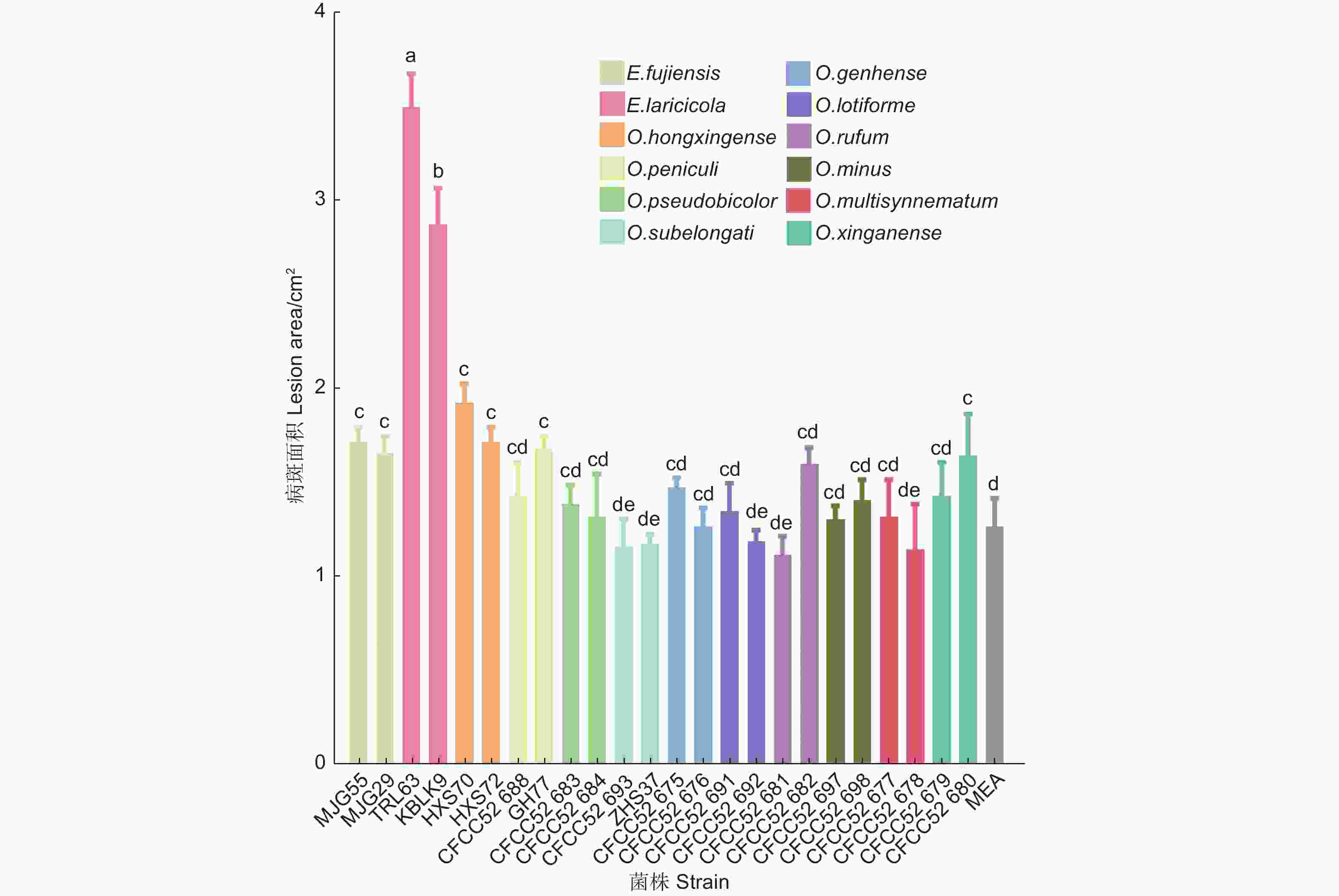

接种两个月后的落叶松没有表现出明显的病害症状和枯萎现象。剥开外层树皮,不同长喙壳菌株接种落叶松后产生的褐色至黑色坏死病斑如图1,病斑面积大小见图2。比较发现,E. laricicola的2个菌株(TRL63和KBLK9)产生的病斑最大,面积分别为3.51 ± 0.18 cm2和2.89 ± 0.19 cm2。单因素方差分析结果显示E. laricicola产生的病斑显著大于其他处理(图2)。E. fujiensis的2个菌株(MJG55和MJG29)、O. hongxingense的2个菌株(HXS70和HXS72)、O. peniculi的GH77菌株和O. xinganense的CFCC52680菌株产生的病斑显著大于对照处理(1.28 ± 0.15 cm2)。其余菌株接种产生的病斑与对照无差异,且接种点中间未呈现坏死状态(图2)。

-

对人工接种产生病斑的病菌再分离和鉴定,得到每个菌株处理的3个随机病变样本平均再分离率为83.3%,证实了落叶松接种点处产生的坏死病斑是由原始接种的长喙壳真菌引起。

-

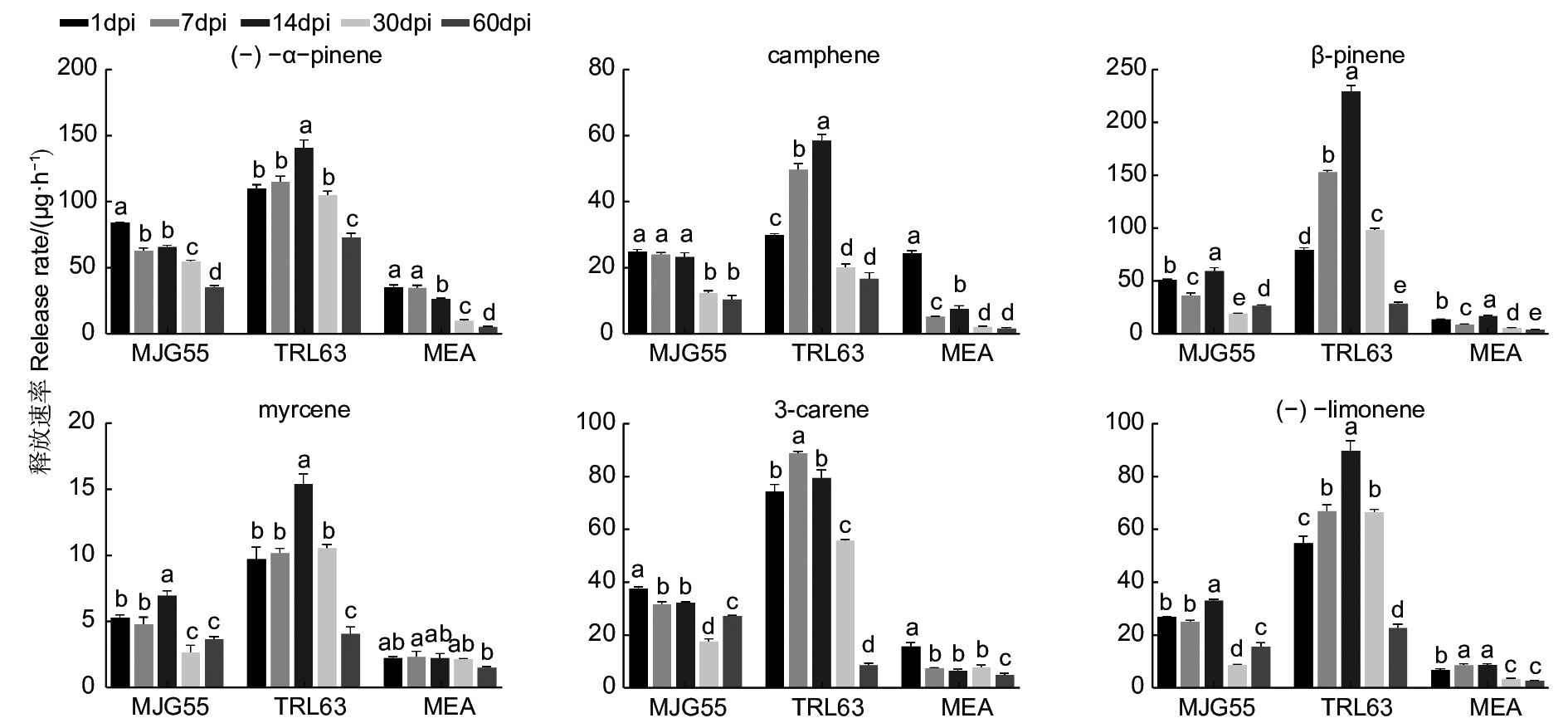

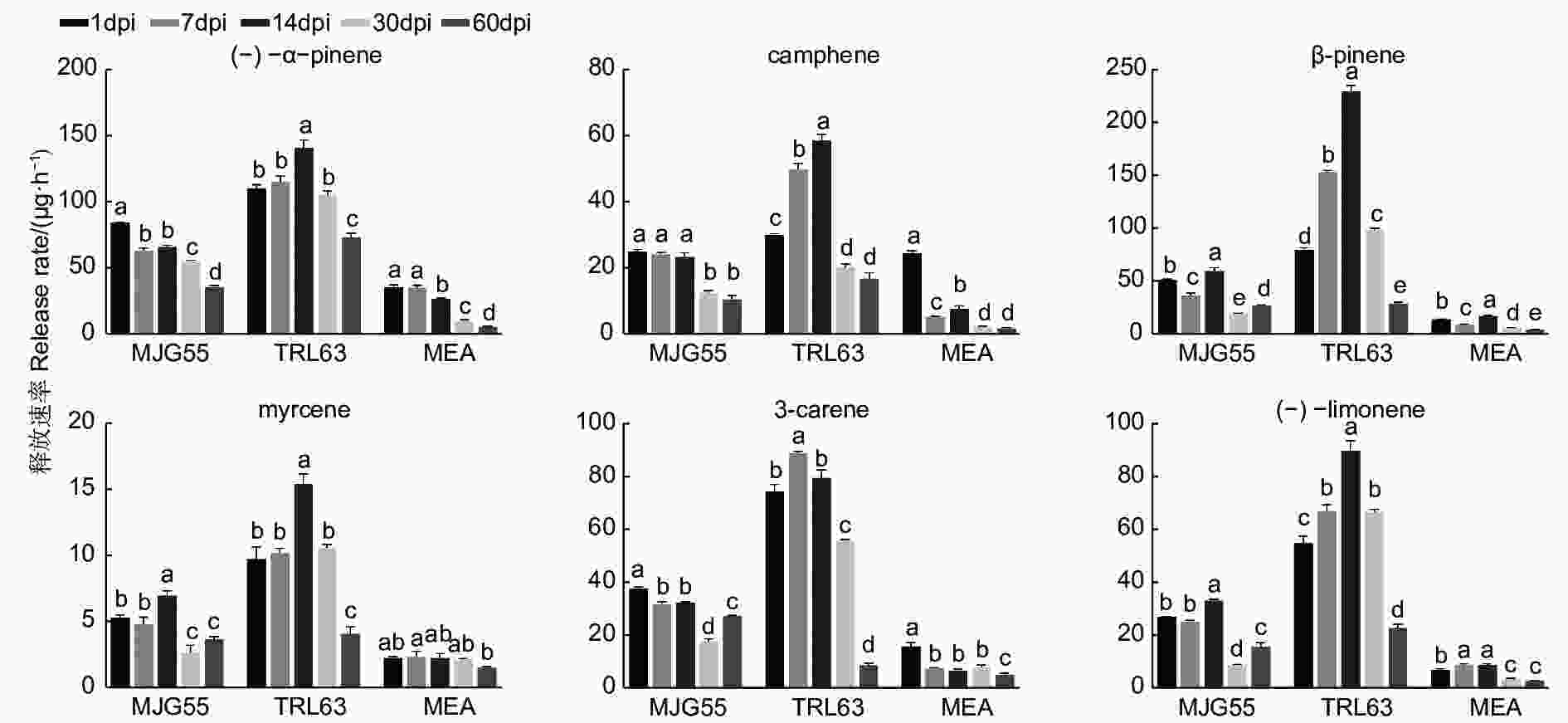

为了研究落叶松对长喙壳真菌的抗性反应,针对接种了E. fujiensis(MJG55)和E. laricicola(TRL63)菌株的落叶松,在接种后的1、7、14、30和60 d分别进行了单萜类物质测定。共检测到(−)-α-pinene、camphene、β-pinene、myrcene、3-carene和(−)-limonene 6种单萜物质,结果如图3所示。总体而言,TRL63处理的单萜释放速率最高,MJG55处理次之,这两种处理与对照均存在显著差异。不同处理后单萜类物质释放速率随时间的变化规律略有不同,TRL63处理中各萜类物质呈现先升高后降低的变化趋势;MJG55和MEA处理的myrcene也呈现先升高后降低的变化趋势,(−)-α-pinene、camphene和3-carene呈现下降的趋势。

-

真菌致病性是指真菌侵染活体植物组织后在其体内存活和发育并引起病害的能力[20-21]。致病性用毒力来量化,毒力是通过测量寄主可视化症状的发展来确定的,包括病斑长度、边材干燥和蓝变面积、树脂反应以及树木的死亡率[22-23]。病斑指寄主植物感染点周围韧皮部组织产生的变暗、凸起或轻微凹陷以及坏死等现象,用于评估真菌对寄主树的影响[24]。长喙壳真菌的致病性一般是通过在成年树或幼苗上人工接种真菌来评估[6, 25-26]。尽管在成年树上接种更接近小蠹虫高密度攻击后的自然接种,但幼苗接种是控制实验环境条件的另一选择[22, 24]。此外,在接种量相当的情况下,幼苗接种更适合于确定小蠹虫伴生长喙壳真菌的毒力[22]。因此,本研究选用5年生的落叶松苗木验证12种落叶松八齿小蠹伴生长喙壳真菌的致病性。结果表明,5种真菌对长白落叶松表现出不同程度的致病力,E. laricicola致病力最强,E. fujiensis和O. hongxingense次之,O. peniculi和O. xinganense较弱(图2),表明这几种真菌对落叶松存在潜在危害风险。其余7种Ophiostoma真菌在接种点处形成的韧皮部变色与对照无差异,未表现出明显致病性。

本研究从亚洲落叶松八齿小蠹虫体上分离到E. laricicola真菌,与之前关于E. laricicola和欧洲落叶松八齿小蠹(Ips cembrae)特异性伴生的认识存在差异[27],这可能是小蠹虫和真菌在扩散中形成了新的伴生关系。Redfern等人最早发现I. cembrae与E. laricicola存在伴生关系,且由这种伴生关系导致的复合侵染使落叶松发生顶梢枯死[28]。E. laricicola能在欧洲赤松韧皮部形成坏死病斑,诱导木质素和树脂的积累,同时减少欧洲赤松细胞壁游离原花青素、低分子量碳水化合物和非木质素成分的含量,表明其能抑制寄主伤口反应早期阶段的木质化,从而延缓寄主对于损伤的自我修复[29]。本研究中,E. laricicola接种在落叶松韧皮部形成的坏死病斑最大,其诱导寄主产生的萜类物质呈现先升后降的趋势,表明该菌具有较强致病力。因此,E. laricicola与亚洲落叶松八齿小蠹形成的伴生关系可能更有利于小蠹虫的入侵,对落叶松造成较强的破坏力。

以前有研究表明,在人工接种条件下E. fujiensis能使30年生的健康日本落叶松死亡[5]。该菌对长白落叶松也表现出一定致病力,并能引起长白落叶松的防御反应[30]。本研究发现,E. fujiensis菌株接种后落叶松韧皮部形成的坏死病斑显著大于对照处理,但与E. laricicola相比病斑较小,在5个调查时间段内大多数萜类物质的变化也较小。这与致病力更强的真菌诱导宿主防御萜类物质发生较大变化的结论一致[16, 18, 31],说明E. fujiensis菌株对长白落叶松的致病力较弱。本文研究结果与Yamaoka[5]和周秀华等[30]的研究结果不同,可能与树木的个体发育有关。有研究发现,与成年树相比,幼树具有更强的化学防御能力,在抵抗病原菌侵染时产生更强烈的抗性反应[32-33]。因此,本研究在5年生落叶松上设定的单一接种量有限,可能不足以造成严重影响,以后将考虑增加接种量。

长喙壳真菌入侵寄主后,寄主体内防御性萜类物质释放增加,这些萜类化合物影响真菌的生长,同时真菌也具有解毒能力,甚至利用寄主产生的防御性化合物。Fang等人研究发现,α-pinene、limonene和carene等8种单萜类物质会抑制E. fujiensis的生长[16]。Cale等人发现,在额外添加α-pinene的培养基上山松大小蠹伴生菌Grosmannia clavigera生长也受抑制[31];而limonene的存在会促进G. clavigera和Ophiostoma ips真菌的生长。此外,不同浓度的萜类对真菌生长的影响也存在差异,如低浓度的myrcene能促进O. ips的生长,而高浓度myrcene对O. ips生长发育无影响[30]。Liu等人认为长喙壳真菌能够利用寄主挥发物中的氮能来促进真菌的生长发育并合成小蠹虫生长发育所必需的麦角甾醇[34]。小蠹虫和长喙壳真菌复合侵染对寄主造成的危害远高于小蠹虫自身钻蛀树木造成的危害[35],因此,研究小蠹虫和伴生真菌的内在联系以及伴生真菌对寄主防御的影响,对于防治小蠹虫暴发危害具有重要理论指导意义。

-

本研究通过人工接种试验发现,小蠹虫伴生长喙壳真菌的不同菌株在落叶松接种点处产生的病斑大小存在差异,有5种长喙壳真菌对长白落叶松表现出不同程度的致病力,E. laricicola菌株致病力最强,E. fujiensis和O. hongxingense次之,O. peniculi和O. xinganense较弱。Endoconidiophora真菌能够诱导寄主产生防御反应,释放的萜类物质增加,且在E. laricicola接种14 d 左右达到峰值。长喙壳真菌被小蠹虫携带至新的寄主植物上,在小蠹虫坑道周围产生的坏死病斑与寄主植物的死亡存在密切关系。本研究通过人工接种长喙壳真菌后测量病斑大小来评估真菌致病力,对于优化小蠹虫综合治理策略提供理论依据与技术支撑。

Pathogenicity of Ophiostomatoid Fungi Associated with Ips subelongatus

- Received Date: 2023-05-12

- Accepted Date: 2023-06-07

- Available Online: 2024-04-27

Abstract:

DownLoad:

DownLoad: